Grades Create Perverse Motives

[Epistemic Status: I wrote this for English Class. I think the ideas are mostly true.]

As I’m starting my senior year of high school and sending off my college applications, I’ve been thinking a lot about how grades change our relationship to our work. While it may seem that grades just evaluate the outcomes of our writing, the grade we get can actually influence our writing and shape it in ways that are incredibly hard to avoid. They subtly change what we write about, but also the style in which we write and prevent us from improving.

Before we talk about their effects, let’s take a look at their uses: how and why are they used in schools? They are convenient: a grade essentially converts a multifaceted paper into a single number that tells how a student did overall. All teachers have to do is read the paper, do some thinking, and then come up with a number. Colleges use them to decide how good of a student you are. All jokes aside, we’re stuck with grades for the time being, so let’s investigate what effect they have on our writing.

When I get an essay back, the first thing I do is look at the number at the end and judge how well I did on it from the grade, not the comments. I’m being irrational here since the comments contain much more information than the grades. They span multiple parts of the rubric and are personalized to my relationship with the teacher. Yet I still look at the grade first and judge myself on it because it’s what I’m conditioned to do, and for some stupid reason, I just care a lot about the number.

Grades also play a part in masking deeper issues in writing with surface level ones. In the “standard” style of five paragraph essays that we all learned in middle school, it’s easier for teachers to focus on – and grade – the structure more heavily than creative ideas. While you might think that some students do need this scaffolding, it actually seems that the ideas, not the style, are more important to develop. In his article “Inventing the University,” Bartholomae observes that “The stages of development that I’ve suggested are not necessarily marked by corresponding levels in the type or frequency of error, at least not by the type or frequency of sentence level errors” (17). A grade easily encapsulates the stylistic and sentence level issues with an essay, yet those errors are the least important. The deeper issues with the creative ideas are much more important, but are harder to correct with a grade than the stylistic issues and show up mostly in the comments (which I’m guessing that most students, like me, should but don’t pay much attention to). Of course, I’m sure some teachers use grades to correct creative ideas, but I suspect, given Bartholomae’s analysis, that most use grades for structure and mechanics, especially since these kinds of writing conventions are more objective and less subject to dispute.

Further, grades change our style and diminish creativity. I’ve been lucky to take honors English classes for the past two years, which means that I’ve had a lot more freedom in my writing. But for many students (past me included), the thought of “I should do this for a grade” sucks all the voice out of writing. We don’t write how we speak but instead how we are taught to write. Bartholomae gives an almost comical exaggerated example of this: “Creativity is the venture of the mind at work with the mechanics relay to the limbs from the cranium, which stores and triggers this action” (5). In most cases, the influence is more mild than in this example, but grades give teachers power over our writing, which can be used for good but is more often than not used to entrench focus on structure rather than creative ideas.

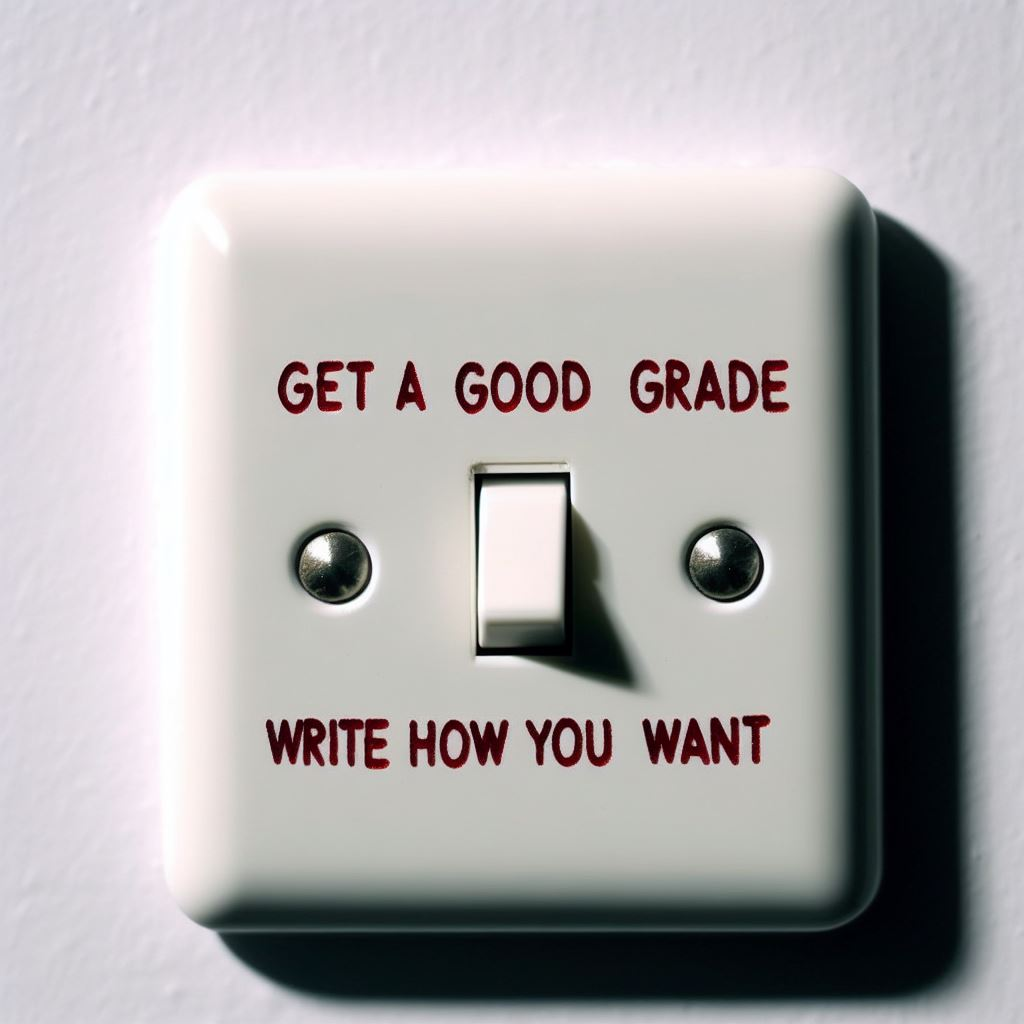

I’m reminded of a similar story that June Jordan told in her article “Nobody Mean More to Me Than You And the Future Life of Willie Jordan.” She was teaching a class about Black English when the brother of one of her students died of police brutality. The class wanted to make a public statement, but they had a choice to make: “Should the opening, group paragraph be written in Black English or Standard English?” (Jordan 371). They really struggled because they knew that choosing Black English would mean that the letter would be dismissed, but more meaningful to them, while one using Standard English might get published but would be using the “language of the killer” (Jordan 372). They chose Black English and didn’t get published. Similarly, when writing for a grade, we often (but shouldn’t) have to choose between writing in a way that we like and writing in a way that will get us a good grade.

In fact, there are even a few changes I’m making to this essay because I’m writing it for a grade. If I were writing just for my blog, I would tell parables and force the reader to make connections between them and my ideas (as I did in this post), but that is just so far from what we do in English class that I fear a lower grade.

Speaking of my blog, I recently rediscovered how much fun writing for oneself can be. Since joining the rationality community and seeing people write about what interests them, I’ve written a few posts about programming and philosophy and posted them to various aggregators. Although I didn’t get a grade, I got something even better – lots of people with more experience than me commenting on my writing. Some agreed wholeheartedly, while some partly agreed; others fully disagreed and thought my ideas were wrong. I don’t gain sentence-level feedback from this process – but as Bartholomae said, that’s not really as important as feedback on the ideas. The lack of a grade allows me to focus fully on the creative idea-level feedback and develop better ideas next time.